The Transformation of Latin America is a Global Advance

The radical tide is about to be put to the test in Brazil and Venezuela. If support holds, it will have lessons for all of us

By Seumas Milne

August 20, 2010 "The Guardian" --Nearly two centuries after it won nominal independence and Washington declared it a backyard, Latin America is standing up. The tide of progressive change that has swept the continent for the past decade has brought to power a string of social democratic and radical socialist governments that have attacked social and racial privilege, rejected neoliberal orthodoxy and challenged imperial domination of the region.

Its significance is often underestimated or trivialised in Europe and North America. But along with the rise of China, the economic crash of 2008 and the demonstration of the limits of US power in the "war on terror", the emergence of an independent Latin America is one of a handful of developments reshaping the global order. From Ecuador to Brazil, Bolivia to Argentina, elected leaders have turned away from the IMF, taken back resources from corporate control, boosted regional integration and carved out independent alliances across the world.

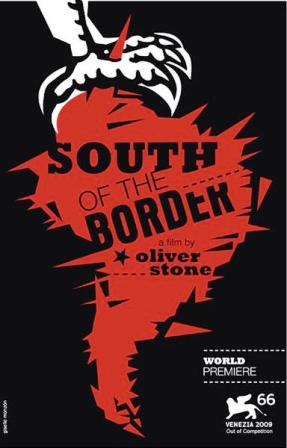

Both the scale of the transformation and the misrepresentation of what is taking place in the western media are driven home in Oliver Stone's new film, South of the Border, which allows six of these new wave leaders to speak for themselves. Most striking is their mutual support and common commitment – from Cristina Kirchner of Argentina to the more leftist Evo Morales – to take back ownership of their continent.

Two crucial votes in the next few weeks will put the future of this process to the test. The first are parliamentary elections in Venezuela, whose Bolivarian revolution has been at the cutting edge of Latin America's renewal since Hugo Chávez was first elected president in 1998. For all his popularity at home, Chávez has been the target for a campaign of vilification and ridicule throughout the US, European and elite-controlled Latin American media – which has little to do with his high-octane rhetoric and much more with his effectiveness in using Venezuela's oil wealth to challenge US and corporate power across the region.

Forget his success in slashing the Venezuelan poverty rate in half, tripling social spending, rapidly expanding healthcare and education, and fostering grassroots democracy and worker participation. Since the beginning of the year Venezuela's enemies have smelled blood as his government faltered in the face of drought-triggered power cuts, a failure to ride out recession with a stimulus package – as Morales's Bolivia did – and growing discontent over high levels of violent crime.

So expect a flurry of new claims that Chávez is a dictator who has stifled media freedom and persecuted bankers and businessmen, and whose incompetent regime is running into the sand. In reality the Venezuelan president has won more free elections than any other world leader, the country's media are dominated by the US-funded opposition, and his government's problems with service delivery stem more from institutional weakness than authoritarianism.

If Chávez's United Socialist party were defeated next month it would certainly put his re-election in 2012 – and Venezuela's radicalisation – in doubt. But that is looking increasingly unlikely. The economy is picking up, a national police force is finally being established and, crucially, Chávez last week dramatically defused the threat of war with the pro-US government in Colombia through a regionally brokered rapprochement.

Even more critical will be the presidential elections in Brazil in October. Brazil's emergence as an economic powerhouse under Lula's leadership has underpinned the wider changes across Latin America. Less radical than Chávez or Morales, the Brazilian president has nevertheless also poured cash into anti-poverty campaigns and provided vital support for the common project of continental integration and independence.

Barred from standing for a third term, he has thrown his popularity behind his chief of staff Dilma Roussef, if anything more sympathetic to the Bolivarians. Unable to attack Lula's economic record, her main rightwing opponent, José Serra, is now effectively running a campaign against Chávez and Morales, denouncing Lula's support for them, his refusal to recognise the post-coup government in Honduras and attempts to mediate between the Iran and the US. So far that looks unlikely to work, and Serra is trailing her badly in the polls.

If both Brazilian and Venezuelan elections are won by the left, the US and its friends may be tempted to look for other ways to divert Latin America from the path of self-determination and social justice it took while George Bush was busy fighting his enemies in the Muslim world. For all Barack Obama's promise to "seek a new chapter of engagement" and warning that a "terrible precedent" would be set if last year's bloody coup against the reforming Honduran president Manuel Zelaya were allowed to stand, there has been little change in US policy towards the region. The Honduran coup was indeed allowed to stand – or, as Hillary Clinton put it, the "crisis" was "managed to a successful conclusion".

The clear message was that the radical tide can be turned and the fear is now that another of the more vulnerable governments, such as Paraguay's or Guatemala's, could also be "managed to a conclusion" in one form or another. Meanwhile the US is attempting to shore up its military presence on the continent, using the pretext of "counter-insurgency" to station US forces in seven bases in Colombia.

But direct military intervention looks implausible for the foreseeable future. If the political and social movements that have driven the continent's transformation can maintain their momentum and support, they won't only be laying the foundation of an independent Latin America, but new forms of socialist politics declared an impossibility in the modern era. Two decades after we were told there was no alternative, another world is being created.

The radical tide is about to be put to the test in Brazil and Venezuela. If support holds, it will have lessons for all of us

By Seumas Milne

August 20, 2010 "The Guardian" --Nearly two centuries after it won nominal independence and Washington declared it a backyard, Latin America is standing up. The tide of progressive change that has swept the continent for the past decade has brought to power a string of social democratic and radical socialist governments that have attacked social and racial privilege, rejected neoliberal orthodoxy and challenged imperial domination of the region.

Its significance is often underestimated or trivialised in Europe and North America. But along with the rise of China, the economic crash of 2008 and the demonstration of the limits of US power in the "war on terror", the emergence of an independent Latin America is one of a handful of developments reshaping the global order. From Ecuador to Brazil, Bolivia to Argentina, elected leaders have turned away from the IMF, taken back resources from corporate control, boosted regional integration and carved out independent alliances across the world.

Both the scale of the transformation and the misrepresentation of what is taking place in the western media are driven home in Oliver Stone's new film, South of the Border, which allows six of these new wave leaders to speak for themselves. Most striking is their mutual support and common commitment – from Cristina Kirchner of Argentina to the more leftist Evo Morales – to take back ownership of their continent.

Two crucial votes in the next few weeks will put the future of this process to the test. The first are parliamentary elections in Venezuela, whose Bolivarian revolution has been at the cutting edge of Latin America's renewal since Hugo Chávez was first elected president in 1998. For all his popularity at home, Chávez has been the target for a campaign of vilification and ridicule throughout the US, European and elite-controlled Latin American media – which has little to do with his high-octane rhetoric and much more with his effectiveness in using Venezuela's oil wealth to challenge US and corporate power across the region.

Forget his success in slashing the Venezuelan poverty rate in half, tripling social spending, rapidly expanding healthcare and education, and fostering grassroots democracy and worker participation. Since the beginning of the year Venezuela's enemies have smelled blood as his government faltered in the face of drought-triggered power cuts, a failure to ride out recession with a stimulus package – as Morales's Bolivia did – and growing discontent over high levels of violent crime.

So expect a flurry of new claims that Chávez is a dictator who has stifled media freedom and persecuted bankers and businessmen, and whose incompetent regime is running into the sand. In reality the Venezuelan president has won more free elections than any other world leader, the country's media are dominated by the US-funded opposition, and his government's problems with service delivery stem more from institutional weakness than authoritarianism.

If Chávez's United Socialist party were defeated next month it would certainly put his re-election in 2012 – and Venezuela's radicalisation – in doubt. But that is looking increasingly unlikely. The economy is picking up, a national police force is finally being established and, crucially, Chávez last week dramatically defused the threat of war with the pro-US government in Colombia through a regionally brokered rapprochement.

Even more critical will be the presidential elections in Brazil in October. Brazil's emergence as an economic powerhouse under Lula's leadership has underpinned the wider changes across Latin America. Less radical than Chávez or Morales, the Brazilian president has nevertheless also poured cash into anti-poverty campaigns and provided vital support for the common project of continental integration and independence.

Barred from standing for a third term, he has thrown his popularity behind his chief of staff Dilma Roussef, if anything more sympathetic to the Bolivarians. Unable to attack Lula's economic record, her main rightwing opponent, José Serra, is now effectively running a campaign against Chávez and Morales, denouncing Lula's support for them, his refusal to recognise the post-coup government in Honduras and attempts to mediate between the Iran and the US. So far that looks unlikely to work, and Serra is trailing her badly in the polls.

If both Brazilian and Venezuelan elections are won by the left, the US and its friends may be tempted to look for other ways to divert Latin America from the path of self-determination and social justice it took while George Bush was busy fighting his enemies in the Muslim world. For all Barack Obama's promise to "seek a new chapter of engagement" and warning that a "terrible precedent" would be set if last year's bloody coup against the reforming Honduran president Manuel Zelaya were allowed to stand, there has been little change in US policy towards the region. The Honduran coup was indeed allowed to stand – or, as Hillary Clinton put it, the "crisis" was "managed to a successful conclusion".

The clear message was that the radical tide can be turned and the fear is now that another of the more vulnerable governments, such as Paraguay's or Guatemala's, could also be "managed to a conclusion" in one form or another. Meanwhile the US is attempting to shore up its military presence on the continent, using the pretext of "counter-insurgency" to station US forces in seven bases in Colombia.

But direct military intervention looks implausible for the foreseeable future. If the political and social movements that have driven the continent's transformation can maintain their momentum and support, they won't only be laying the foundation of an independent Latin America, but new forms of socialist politics declared an impossibility in the modern era. Two decades after we were told there was no alternative, another world is being created.